Mosquitoes

Every now and again, during the summer months, we get a periodic spike in mosquito numbers on the peninsula. Mosquitoes are annoying and can also be carriers of disease. They have always been prevalent in this area, especially in late summer and early autumn and some years are worse than others.

It would be interesting to know how the Aboriginal people who lived here for thousands of years coped with mosquitoes. The shell middens and engravings at the Daleys Point site indicate that they collected food from Cockle Bay and camped on the ridge above. One of the first European observers (Collins) reported that Aboriginal people had smeared fat and oil on their skin and he believed this was to protect them from mosquitoes.

Mosquitoes in this area pose only a minimal risk of disease. The mosquito monitoring program conducted by NSW Health at Killcare Heights and Empire Bay has not detected any carrying Ross River virus and only very occasional detection of Barmah Forest virus. These are the most common mosquito borne viral diseases in Australia. Both are debilitating but not fatal and the infection rates are low.

Although this monitoring has detected about 15 species of mosquitoes, only 2 species occur in appreciable numbers - the Saltmarsh Mosquito (Ochlerotatus vigilax) and the domestic container mosquito (Ochlerotatus notoscriptus). It is the Saltmarsh mossie that spikes in numbers.

Between the Liberty and the Empire Bay turnoff, the Cockle Bay Wetlands and Nature Reserve are a hidden gem. The best access is on the track opposite Empire Bay Primary school behind the interpretation board. The Nature Reserve was established in 1992 to protect “the most important areas of unspoilt wetland within the Brisbane Water area”.

Most significant are its saltmarshes. Saltmarshes are globally threatened and have been declared an endangered ecological community in NSW. They contain a unique flora, provide habitat for migratory birds and a rich feeding area for fish. The Reserve is home to threatened species: in addition to the 6 vulnerable species of microbat there are yellow-bellied gliders, squirrel gliders, the eastern chestnut mouse, regent honeyeaters, osprey and the bush-stone curlew.

It would be interesting to know how the Aboriginal people who lived here for thousands of years coped with mosquitoes. The shell middens and engravings at the Daleys Point site indicate that they collected food from Cockle Bay and camped on the ridge above. One of the first European observers (Collins) reported that Aboriginal people had smeared fat and oil on their skin and he believed this was to protect them from mosquitoes.

Mosquitoes in this area pose only a minimal risk of disease. The mosquito monitoring program conducted by NSW Health at Killcare Heights and Empire Bay has not detected any carrying Ross River virus and only very occasional detection of Barmah Forest virus. These are the most common mosquito borne viral diseases in Australia. Both are debilitating but not fatal and the infection rates are low.

Although this monitoring has detected about 15 species of mosquitoes, only 2 species occur in appreciable numbers - the Saltmarsh Mosquito (Ochlerotatus vigilax) and the domestic container mosquito (Ochlerotatus notoscriptus). It is the Saltmarsh mossie that spikes in numbers.

Between the Liberty and the Empire Bay turnoff, the Cockle Bay Wetlands and Nature Reserve are a hidden gem. The best access is on the track opposite Empire Bay Primary school behind the interpretation board. The Nature Reserve was established in 1992 to protect “the most important areas of unspoilt wetland within the Brisbane Water area”.

Most significant are its saltmarshes. Saltmarshes are globally threatened and have been declared an endangered ecological community in NSW. They contain a unique flora, provide habitat for migratory birds and a rich feeding area for fish. The Reserve is home to threatened species: in addition to the 6 vulnerable species of microbat there are yellow-bellied gliders, squirrel gliders, the eastern chestnut mouse, regent honeyeaters, osprey and the bush-stone curlew.

Saltmarsh is a vegetation community that lies just above the mean high tide mark. It is dominated by hardy, salt tolerant plants such as Samphire. It is inundated only occasionally by the high spring tides and in the meantime it dries out, concentrating the salt to levels that even mangroves can’t tolerate. (See http://www.killcarewagstaffetrust.org.au/saltmarsh-and-mangroves.html for more info)

Saltmarsh Mosquito

The female saltmarsh mosquito lays its eggs on drying soil and at the base of vegetation on the edge of depressions in the saltmarsh. These then dry and become dormant. A couple of king tides at the right time floods the saltmarsh leaving the pools of water that the mosquito larvae need to survive. Heavy rain can also provide the necessary pools. Although the breeding occurs in Cockle Bay and Empire Bay it appears the adults head for the hills and spread across the Bouddi peninsula.

There have been plenty of studies that have documented mosquitoes in the diet of a range of animals such as fish, frogs, lizards, birds and bats. The importance of mosquitoes in the diets of these animals is uncertain. What is certain, however, is that these animals are an integral part of that important ecological community.

After each spike in mosquito numbers there is always some discussion about mosquito control. Council has examined the options from time to time. The serious contenders are problematic. A bacterium (Bti)that disrupts the gut of the larvae can be sprayed over the wetlands. This is very expensive and has to be done within a very short window of time so has a high failure rate. Another biochemical method is to spray methoprene that disrupts the growth of all insect larvae. It is toxic to fish and other aquatic life.

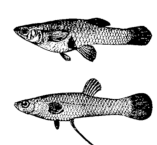

There have been some spectacularly misguided attempts at mosquito control. During the 1940’s the government spread the Mosquito Fish or Plague Minnow (Gambusia holbrooki), a native of North America, into as many east coast waterways as possible as a control agent for mosquitoes. It didn’t work and now this fish is recognised as an aggressive and voracious predator. Research has documented its impact on fish, invertebrates and frogs including a link to the decline of the Green and Golden Bell Frog (Litoria aurea).

The female saltmarsh mosquito lays its eggs on drying soil and at the base of vegetation on the edge of depressions in the saltmarsh. These then dry and become dormant. A couple of king tides at the right time floods the saltmarsh leaving the pools of water that the mosquito larvae need to survive. Heavy rain can also provide the necessary pools. Although the breeding occurs in Cockle Bay and Empire Bay it appears the adults head for the hills and spread across the Bouddi peninsula.

There have been plenty of studies that have documented mosquitoes in the diet of a range of animals such as fish, frogs, lizards, birds and bats. The importance of mosquitoes in the diets of these animals is uncertain. What is certain, however, is that these animals are an integral part of that important ecological community.

After each spike in mosquito numbers there is always some discussion about mosquito control. Council has examined the options from time to time. The serious contenders are problematic. A bacterium (Bti)that disrupts the gut of the larvae can be sprayed over the wetlands. This is very expensive and has to be done within a very short window of time so has a high failure rate. Another biochemical method is to spray methoprene that disrupts the growth of all insect larvae. It is toxic to fish and other aquatic life.

There have been some spectacularly misguided attempts at mosquito control. During the 1940’s the government spread the Mosquito Fish or Plague Minnow (Gambusia holbrooki), a native of North America, into as many east coast waterways as possible as a control agent for mosquitoes. It didn’t work and now this fish is recognised as an aggressive and voracious predator. Research has documented its impact on fish, invertebrates and frogs including a link to the decline of the Green and Golden Bell Frog (Litoria aurea).